- Jul 18, 2025

- 6 min read

In my senior year of high school, some friends suggested we all go get something to eat and go see a movie. At the fast-food joint, I was more fascinated that a friend of mine liked pepper on his French fries than what we were about to see—some cheerleader movie called Bring it On which I expected to hate. I’m fairly sure I was just going along for the ride, something to do. What I saw, instead, was one of the most quotable teen comedies ever, only to be replaced four years later by Mean Girls.

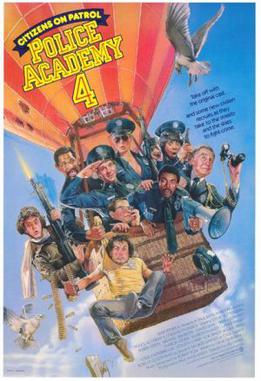

While writing last week’s non-guilty pleasure essay on the Police Academy franchise, I had no need to go back and watch the movies. I know them scene by scene. But, when I realized my other guilty pleasure franchise began with Peyton Reed’s Bring it On, I was compelled to rewatch at least the first through third films. I suppose I should be slightly embarrassed being in my early forties and loving a film series about cheerleaders, but it’s not as if the actors in these films were teenagers. Like Saved by the Bell and other teen fare, young twenty-year-olds who look nothing like teens portray the high schoolers. So, frankly, if there’s judgment, I would judge the judger, whose mind must be sicker than mine.

But pretty women are far from the only reason to love these movies. Jessica Bendinger, the screenwriter of the original (who later wrote and directed the criminally underrated gymnastic comedy Stick It) helped create a perfect movie. While there are the usual comic complications, the original Bring it On is picture-perfect—fast, funny, energetic, full of fun music, and (of course) spirit fingers.

It is also, in its own way, dealing with a serious subject—that of privileged teens in predominantly white areas of California competing against inner-city, mostly black areas of L. A. When Kirsten Dunst’s cheer captain realizes all the routines her inherited team have been doing have been ripped off by a much better squad, her life is shattered. It is not played by Dunst for laughs. There is a moment when she is riding back to San Diego with Eliza Dushku (one of my favorite actresses) and says, “I am just cheerleading.” In most movies, this would be ironic, and you would laugh. But, performed by a great actor, there’s some kind of un-ironical seriousness that makes you root for her.

Now, what do I mean when I say Bring it On is a perfect movie? Yeah, it’s no masterpiece, but can we call it the Godfather of cheerleading movies? When 2009’s Fired Up!, another underrated movie, explored a cheerleading camp in which all the attendees can quote every line, almost cult-like, there is some truth to this. Fired Up! is a parody, but its worship of Bring it On, while amusing, is apt because the movie is hilarious, engaging, as said above infinitely quotable and, dare I say it, even life-affirming?

When the original more than doubled its budget, sequels were inevitable. The results have been in the original spirit to barely entertaining and, yet, because they stem from a great movie, they are watchable in their own way. Okay, only one is truly watchable—and we’ll get to that. But just like with Police Academy sequels, they have their own surprises.

Four years after the original, the first in many direct-to-DVD sequels began. While Bring it On Again shares the same producers (and nothing else), it is a completely different story. Well, actually, it’s the same story except this time it’s about college cheerleading. It suffers from being perhaps the least funny of any of the movies. You can tell fairly on when the Dean of California State College cuts funding from almost every department except its seven-time National Championship winners, the cheerleading squad, run by a true villain, played by Bree Turner. The original film had no villains, just two teams vying for the same spot—being the best. In this one, the Dean is a cartoon character, the two leads are completely nondescript, (the DVD cover showcases the minor character of Monica in the foreground, but the film’s “star” is Anne Judson-Yager who does not have a Wikipedia page and that’s probably for the best), but, watching it again, there were two things that did stand out: 1) there’s an activist student who does nothing but grumble about the patriarchy and pout (so, a prediction of our present time of whining, I suppose) and 2) one truly wonderful moment. I can’t tell you exactly how many times I’ve said, “Don’t be all up in my Kool-Aid,” but I can at least thank the movie for that.

Now for the switcheroo. Bring it On is a perfect movie, but Bring it On: All or Nothing is my personal favorite (like I prefer Police Academy 4 to 1). I would say it’s just as quotable and even manages to go deeper into the original racial tensions than the first movie as Hayden Panettiere’s character is forced to move to an inner-city school and somehow meld with a squad that breaks boundaries in lieu of being champions. The film is a delight despite the presence of Solange Knowles-Smith as the team captain; Solange, like her sister Beyoncé, cannot act. That being said, it does better than its predecessor in having more than one funny line, my particular favorite being, “Some of my best friends live next door to black people.” How these films are looked at now in our polarized, tribalistic age, I don’t know. But I still enjoy them. The third film also matches the feel of the original too in its use of pop music, especially the early work Rihanna (when it was fun) and Gwen Stefani in her “Hollaback Girl” phase.

The next film was Bring it On: In it to Win It. While it is directed by the same director as All or Nothing, it doesn’t have half the energy which is most likely due to a sad “Jets vs. Sharks” plot (literally) and lackluster performances by Ashley Benson, Cassie Scerbo, and Jennifer Tisdale. This is the Bring it On film that most feels like a Hallmark movie with its romance subplot. While third film could said to be shameless because Rihanna is featured because the grand prize is dancing with her in an alternative version of “Pon de Replay,” this one is a lot more shameless, tying in its parent company’s resort (Universal Orlando) and Ashley Tisdale, sister of Jennifer, who was attempting a solo career at the time and appears in the film.

The last of the original five (which should have been enough) was Bring it On: Fight to the Finish. It’s not a bad movie. Christina Millian stars and provides music. They really tried with her, but she just never caught on like most of her contemporaries. It is nice to see the film explore more of a Latin feel (though Leti’s presence in All or Nothing is a lot more fun), but otherwise it is a swap on All or Nothing with an inner-city girl going to a pristine WASP school. It is the point in the series where treading water was the way.

I’m embarrassed to say (or perhaps I shouldn’t be) that I have not seen the last two in the series, Bring it On: Worldwide Cheersmack, which was made a full eight years after Fight to the Finish, nor the “horror” spin-off Bring it On: Cheer or Die. I’m almost tempted to be cheersmacked because Vivica A. Fox, one of my favorite comic actresses, is in the movie, but being not much of a horror film fanatic, the likelihood of seeing Cheer or Die is slim. Though, who knows? Maybe in October, it could be a fun watch.

Cheerleader movies have a reputation for being exploitative and prurient, going back to the drive-in theaters of the 1970s. While there is a lot of sexual humor in the Bring it On films, I don’t think they fit into that category. They are fun and they especially enjoy lampooning that one girl in high school everyone hates from Whitney in the first one to Winnie in the third. The films are about being one’s self, breaking down barriers, and joy. That is why they are in another of my series of “non-guilty” pleasures. And, if you don’t like it—well, this is my website and it is not a cheerocracy.